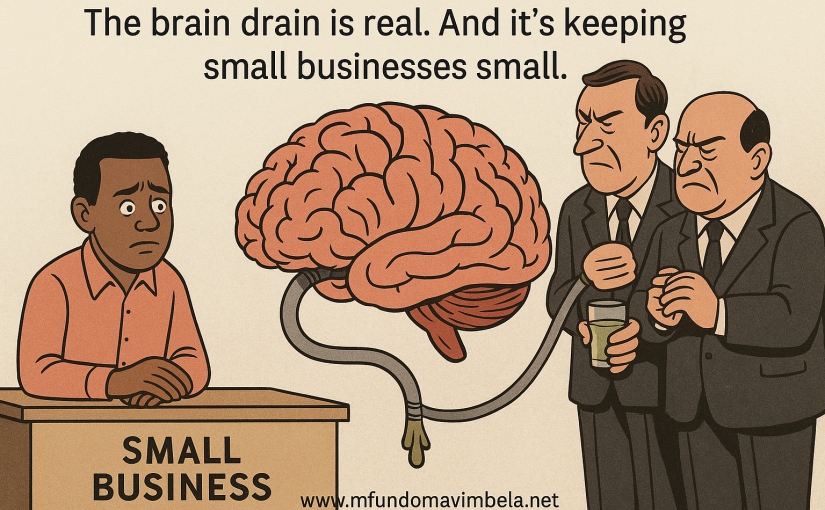

There’s a cycle playing out in SMEs across the country that nobody wants to talk about. It’s not about lack of funding, market access, or government support—though those are real issues. This is about something more insidious, more personal, and frankly, more heartbreaking for those of us running small businesses.

We’re training the workforce for corporates. And we’re doing it at our own expense.

The Investment Nobody Sees

Picture this: A young person walks into your office. Fresh out of school, maybe a diploma or degree in hand, but zero practical experience. The big companies won’t touch them—no experience, they say. But you see potential. You see hunger. So you take a chance.

For the first six months, they’re a net loss. Mistakes everywhere. You’re correcting their work, redoing presentations, holding their hand through client interactions. You’re paying them a salary while essentially running a private training academy. But you persist because you remember when someone gave you a shot.

By month twelve, they’re starting to get it. Fewer mistakes. Better output. You can actually delegate without holding your breath.

By year two, something magical happens. They’ve become competent. Confident, even. They’re producing work that actually moves the business forward. They’re handling clients. They’re solving problems independently.

And then they resign.

The Cruel Mathematics of SME Development

Here’s what that journey cost you: Two years of salary. Hundreds of hours of mentorship and training. The opportunity cost of projects you couldn’t take on because you were busy teaching. The client goodwill you burned through while they learned on the job.

Just when you’re about to recoup that investment—just when they’re finally adding more value than they’re consuming—they’re gone.

The resignation letter is always polite. They’re grateful for the opportunity. They’ve learned so much. But they’ve received an offer they can’t refuse. Better benefits. Career progression. A fancy job title.

From a corporate.

The Corporate Playbook

Let’s be clear about what’s happening here. This isn’t accidental. Corporates have mastered the art of talent acquisition from SMEs. They’ve figured out that we do the hard work of development, and they can simply cherry-pick the results.

But here’s where it gets particularly painful: Sometimes they don’t even wait for the resignation. They engineer it.

You land a contract with a big company. Fantastic news. You assign one of your rising stars to the project. They deliver. The corporate client is impressed. The contract period ends.

Then comes the corporate job offer. Direct to your employee.

The contract doesn’t get renewed. But your employee does—as their employee.

You’re left with a gap in your team, lost institutional knowledge, and the bitter taste of having been used as a free recruitment and training agency.

Why This Matters Beyond One Business

This isn’t just about hurt feelings or business frustration. This cycle is one of the fundamental reasons why SMEs struggle to scale. How do you grow when you can’t retain institutional knowledge? How do you build capacity when your capacity keeps walking out the door just as it matures?

Every time we lose a trained employee to a corporate, we’re not just losing a person. We’re losing:

- The systems and processes they learned to navigate

- The client relationships they built

- The industry knowledge they accumulated

- The mistakes they already made (and learned from)

- The investment of time and money we poured into their development

We’re reset to zero. Again. And again. And again.

Meanwhile, corporates build on the foundation we laid, enjoying the benefits of employees who already know how to work, how to think, how to solve problems—all skills honed in our small businesses.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Young professionals stay in SMEs while they’re unsure of themselves. The moment confidence kicks in, the moment they realize their worth in the market, they’re gone. And who can blame them? We can’t compete with corporate salaries, benefits, and brand names.

But let’s call this what it is: An exploitative system where SMEs serve as the training ground for corporate talent pipelines, bearing all the cost and reaping almost none of the long-term benefit.

A Different Way Forward

Corporates, here’s a radical idea: Instead of poaching talent from the SMEs you work with, how about acknowledging the role we play in developing that talent?

When you identify exceptional people working for your SME suppliers, extend the contract with the SME. Increase the rates to account for the value that trained professional brings. Build long-term partnerships that recognize the investment SME owners make in developing talent.

Is this a pipe dream? Probably. Does it go against every instinct of corporate cost management and talent acquisition strategies? Absolutely.

But until something changes—until there’s recognition and respect for the role SMEs play in workforce development—we’ll remain stuck. Training staff we can’t keep. Starting over every two years. Never quite growing beyond “small” because we’re constantly rebuilding our foundation.

This is one of the many reasons SMEs struggle to graduate from startups to sustainable businesses. Not lack of ambition. Not lack of skill. But a system that extracts value from us without compensation, recognition, or even basic acknowledgment of what’s happening.

The brain drain is real. And it’s keeping small businesses small.